In late December, for a few years now, I have tweeted out a big list of albums I enjoyed. On Thursday, I posted my picks for 2021, some of which were likely not a surprise for anyone who follows me on Last.fm. This spring, I reactivated my account there and began scrobbling again after years away in the pursuit of better music recommendations. I am not sure it is working, but here is what I have found so far.

Apple Music is a remarkable deal for me: spending ten bucks a month gives me access to almost any record I can think of, often in CD quality or better. There are radio features I do not use and music videos I rarely watch, but the main attraction is its vast library of music. Yet, with all that selection, I still find new music the old-fashioned way: I follow reviewers with similar tastes, read music blogs, and ask people I know. Even though Apple Music knows nearly everything I listen to, it does a poor job of helping me find something new.

Here is what I mean: there are five playlists generated for me by Apple Music every week. Some of these mixes are built mostly or entirely from songs it knows I already like, and that is fine. But the “New Music Mix” is pitched as a way to “discover new music from artists we think you’ll like”. That implies to me that it should be surfacing things I have not listened to before. It does not do a very good job of that. Every week, one-third to one-half of this playlist is comprised of songs from new albums I have already heard in full. Often, it will also surface newly-issued singles and reissued records — again, things that I have listened to.

When I scroll down to the “New Releases” section on the “For You” page, it is an even sadder story. Perhaps I have this all wrong, but this seems to me like it should be where I learn about new albums from artists I already listen to. I can remember just one time since Apple Music launched when this section matched my expectations for it. At all other times, it shows weeks-old records I have not played from artists I have not heard of. And they just sit there for weeks, unplayed, until another set of similarly-confusing picks is displayed. Have I got the concept of “New Releases” completely wrong?

Shallowest of all are the “Similar Artists” recommendations on every artist’s page. It tends to prioritize proximity to the selected artist, so it often shows side projects and solo acts. For example, according to Apple Music, artists similar to Soundgarden include Chris Cornell — who was Soundgarden’s lead singer — and Temple of the Dog — one of his side projects — and Audioslave — another Cornell project. It also suggests Alice in Chains, Stone Temple Pilots, and Pearl Jam, three other bands with similar tonal qualities. How many listeners of Soundgarden are there in 2021 who do not know about any of these other bands and projects? I would wager it is a tiny number given Soundgarden’s fame and fanbase. I suppose there are some people who are not fans, per se, and would appreciate these recommendations. But why is Apple Music showing me those artists when I have listened to them all in Apple Music?

In fairness, the artist pages are distinct from the “For You” section of the app. Yet, surely the entire service should be tailored for me. Otherwise, what is the purpose of the algorithmic backend?

You may rightfully ask why I have not stopped using Apple Music and switched to, for example, Spotify, which has far better recommendations. The answer is because I have an anachronistic setup of mostly local music that I would like to keep syncing to my iPhone, and I still do not trust any of the matching or cloud syncing features to do that job for me, including Apple’s.

So: Last.fm. There are a few things I like about it. First, it seems to take into account my entire listening history, though it does give greater weight to recency and frequency. Second, it shows me why it is recommending a particular artist or album. Something as simple as that helps me contextualize a recommendation. Third, its suggestions are a blend of artists I am familiar with in passing and those that I have never heard of.

Most importantly, it feels free of artificial limitations. Apple Music only shows a maximum of eight similar artists on my iPhone, but there are pages of recommendations on Last.fm. Echo and the Bunnymen has twenty-five pages with ten artists each. I can go back and see my entire listening history since I started my account there. Why can I only see the last forty things I listened to on Apple Music?

There are so many things Apple could learn from Last.fm’s recommendation approach, and I wish it would. Right now, its approach is somewhere between inconsequential and unhelpful. It does not have to be this way, and it should not be this way.

Maybe part of my appreciation comes from my nostalgia for the mid-2000s internet era. They are memories of shiny, colourful logos, wet floors everywhere, and new social networks for every conceivable interest. These websites encouraged centralization and many were ultimately destructive to privacy, but there were also gems like Last.fm. It was built around a simple premise: track your music listening history for better recommendations.

It still feels like an artifact of a simpler era. While Apple is busy rebuilding Music in MacOS so it feels less like a weighty mess, Last.fm still feels like a breath of fresher air. I am not calling it lightweight — it is still a web app, so that would be ridiculous — but it does not feel as ponderous as Apple’s attempts. I wish Apple could capture a bit of that magic, if only because Music is still used every day on all of my devices.

In the meantime, I will keep tracking my library with Last.fm. It feels a little quaint, a little cute, but I like it. On my Macs, I use NepTunes; on my iPhone, I use Soor. Both are very good.

I sent the project manager a spreadsheet filled with edits and tracked defects.

Client: “Oh, look at all the nice red and greens. Such nice Christmas colors, very festive of you!”

Me: “Thanks, ’tis the season. But the red means there’s a problem, and the green are values that need to be filled in.”

One of the projects I did at a big company once upon a time was evolving organically, and we eventually realized we needed a "dashboard" of sorts. That is, we wanted an internally-hosted page that would let anyone load it up and see what was going on with the service. It was intended to be simple: ping our server, ask for the status, and then render the response into a simple list. Later on, we knew we were going to want to add the ability to send a "panic" signal to our server from this page, so that anyone in the company could hit the "big red button" if things went haywire.

This, then, is a story of trying to make that status page happen at a big company. I'm going to use dates here to give some idea of how long a single task can drag on. We'll start from January 1st to make it easy: dates are correct relative to each other here.

January 1: we put up a terrible hack: a shell script that runs a Python script that talks to the service to get the status and then dumps out raw HTML to a file in someone's public_html path.

January 29, early: there's this team that nominally owns dashboards, and they got wind of us wanting a dashboard. They want to be the ones to do it, so we meet with them to convey the request. We make a mockup of the list and the eventual big red button to give them some idea of what it should look like.

January 29, late: asked "dashboard team" manager if they had been able to get the network stuff talking to our server yet via chat. No reply.

February 13: random encounter with that manager. Asked about it. Our dashboard "is on the roadmap now".

February 14: an added detail: "no telling when, though"

February 20: still waiting around for something to happen.

March 20: I mention to the rest of the group how I'm losing faith in that dashboard team. "Pretty sure we're going to need to hack up a terrible page to get them moving on this".

March 24: talking to the group again: "we still don't have a status page", and "how long does it take to make a single page?"...

March 25, early morning: I hit the wall and start doing it myself. It means writing code in a language I never use, with frameworks I have never seen before, dealing with data structures that are completely foreign. It's slow going. I have to ask questions that probably seem stupid to most people because this frontend stuff is SO not my domain. My first iteration doesn't even talk to the server: it just has a bunch of data hard-coded and is all about writing the renderer to spit out a list.

March 25, mid-morning: someone notices that one of the necessary steps to talk to the server from the frontend side of the world was never done, because we're having to do it right now to get my terrible new code to work. That is, you have to basically copy across some RPC definition type stuff to talk cross-systems, and they would have needed that as soon as they started messing around in the problem space.

The fact it's never been copied across means that nobody ever even started looking at things. It's one of those things that takes like five minutes and lets you continue with the rest of the project. This spawns the notion of a "canary macguffin" - a critical early step in the project that never happened, so you can tell that nobody ever got that far.

March 25, early afternoon: having synced the RPC stuff, the network I/O now works, and the terrible code written in this crazy moon-man language and frameworks is now talking to production and getting Real Data.

March 25, mid afternoon: and now it's a page that other people can load up from my testing server instead of being a lump of stuff on disk that only I can run.

March 26, morning: all of the "finishing touches" that need to exist on an internal page are added: security context stuff, permission domain stuff, that sort of thing. The code is split into functions so it won't be a giant stream-of-consciousness top-to-bottom blob of garbage. Various people take pity on me and help me understand how to make it sort server-side so it doesn't load up, then freeze the browser while some JS code sorts it on the client. They also help me understand a bunch of data structure/framework stuff that is completely foreign to me.

March 26, mid-afternoon: code ships and is online for anyone in the company to see. It's just a status page (no big red button), but this means we can now kill the terrible shell+python thing that's been running every two minutes in a screen session all this time.

March 26, late afternoon: I told the dashboard team that we went and did it ourselves. I am advised that the person nominally assigned the task "hasn't even started designing it yet".

March 30: dashboard team manager randomly drops by my desk and is suddenly *very* interested in the terrible page we wrote, and asks what else we need. I advise that we need the big red button that lobs a "panic" RPC at our server. Manager advises they will "bring the details to (the assignee)".

April 8: it seems there's now a mock-up of sorts from the team. Inside the group, we start talking about that situation where if you mail the $open_source_project mailing list asking for help with a legitimate problem, nothing happens, but if you make up a shitty version of something and fire it off, then suddenly 50 million people show up and go OI! DO IT THIS WAY! But, three months earlier when you politely asked for help, zip, nothing, nada, zilch.

April 14: someone points out they've Done Something to the page, and oh no, what have they done? The existing page now has this godawful rendering of a very large piece of equipment. Put it this way, if the project's codename was "bulldozer", there was now a little graphical bulldozer up at the top of the screen, complete with all of the other crap that you'd expect to see around a bulldozer.

Also, this isn't just a PNG or something. It's not some stock artwork, and it's not something someone drew. Oh no. This thing is a whole pile of CSS crap that manages to spit out a *dynamic rendering* of the damn thing.

So nothing happens for months, then two weeks after we ship something terrible to show how it's done, they now have time to go and screw around with this ridiculous (and ugly) thing? What?

The group's chatter continues. "This is what they spent time on?", and "We don't have a big red button, but we sure as hell have a CSS-ified bulldozer", and "how long do you think that took", and finally "if it was longer than 30 minutes, we got ripped off".

April 27: the all-CSS-bulldozer-thing disappears from the top for those of us in the group, because they do something to exclude us from seeing the new rendering, so at least we don't have to look at the damn thing and be reminded of how badly this is going.

May 14: still nothing useful to report. The page is now in tatters: what was a single file is now split across multiple things of different types: frontend framework A, frontend scripting language B, and so on. We ponder just reverting the whole mess to get it back to a simple single file that we actually understood and could work on.

June 3: meeting with the dashboard team manager in which we ask why they put a CSS bulldozer on top of the page and still haven't given us the big red button, which we actually need to keep production safe. The response: the person assigned to the project went off to spend a month doing something else on some other team.

I may have said something like "it's like you asked me to clean up the parking lot and I just decided to paint my nails first".

We pointed out that this was not a request for priority. We are just going to end up doing it ourselves. We just can't understand why all of this stuff was done and just dumped there. It was one simple file... and now it's *five*. The official answer is "this is the only way we can maintain it".

Finally we pointed out that this is customer feedback: i.e., you've already lost my business, please don't rush to save it now. You should take this feedback and recalibrate so as not to leave future people in the lurch like what happened here.

Someone noted that it would probably have been okay if the person went "here's your button and by the way we added pretty things". Instead, it turned into "look how I amused myself, made you wait for months, and did nothing to improve your experience, but I had fun and that's the important part".

June 4: manager goes and writes the panic button thing.

June 13: turns out, no, wait, the button is there, but it doesn't ask for confirmation (as we had asked), and... it didn't send the RPC to our server, so it didn't actually DO anything. It was just an image or something!

June 17: someone on the team reports that the button now works.

So, whenever you wonder what it's like at a big company... sometimes, it's like this! And, hey, sometimes it's even worse!

Enlarge (credit: peng song / Getty)

After the California Gold Rush, in 1870, two Kentucky swindlers whipped up a scheme to prey on thirsty financiers’ FOMO. They invented a diamond field out West. Investors sunk millions in today’s money into the scheme. All of it, of course, was for naught—a cautionary tale about believing anyone who claims they have a surefire plan to get rich quick.

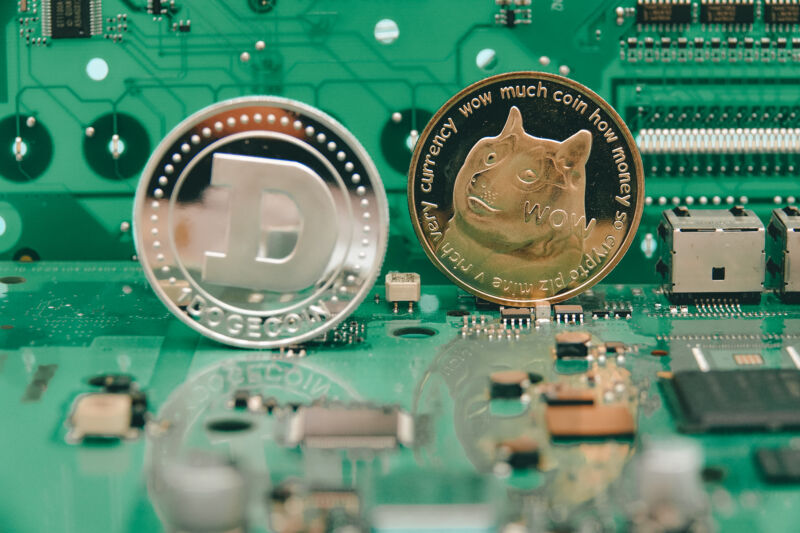

A hundred and fifty years later, a new generation of amateur investors is equally desperate not to miss the next big thing in the finance world. After watching the great GameStop stock boom play out on sites like Reddit and Discord this winter, hundreds of thousands of hopefuls are joining Discord groups that promise big earnings from manipulating the crypto market—also known as crypto pump-and-dumps. Step 1: Buy in early, when the coin is low. Step 2: convince other people to join you—the more, the merrier, the bigger the potential gains as the price of the coin goes up. Step 3: Sell out before the price tanks. Get the timing right, these groups promise, and you come out a winner (and richer). Losers are left holding the bag.

There are two facts that I have sometimes found it difficult to reconcile. The first is that Tesla, Inc. makes innovative and genuinely impressive electric vehicles that can hold their own against the fastest performance cars in the world. The second is that the CEO of Tesla, Inc., celebrated entrepreneurial genius Elon Musk, is a liar, huckster, and moron, who regularly says things so ignorant that I cannot understand how they can come from a human adult, let alone one treated by his fans as a super-genius. Is one of these facts untrue? Are Tesla’s cars actually bad, their deficiencies carefully covered up and their quality over-hyped? Is Elon Musk actually not a liar, huckster, or moron? If you look more closely, are things that look like fraud and stupidity to me actually signs of brilliance? Or is there a way for both facts to be true?

It turns out it’s all true. The cars are impressive and their flaws get covered up. Musk is a lying ignorant grifter and he has inspired innovation in the electric car industry. Understanding that these seemingly contradictory things can be true simultaneously is important, because societies who cannot hold these two ideas at the same time may end up following scam artists and false prophets off the cliff and into the abyss.

Musk’s tenure as CEO has seen Tesla become the most valuable automaker in the world and has made Musk one of the richest people on Earth, if not the richest. He is treated in the press as a tech visionary who dreams big. Every few months he announces some seemingly hare-brained scheme and pundits sing its praises without much scrutiny about whether it could work. The Simpsons, in a sign of the show’s declining satirical bite, portrayed him not as the second coming of monorail salesman Lyle Lanley, but a brilliant rocket scientist, “a being with intelligence far beyond ours,” “possibly the greatest living inventor.”

Now that the president of the United States is no longer a climate change denier, and there may be some kind of broad national effort to electrify American transit, Musk may take on an even more important role in shaping our national vision for transit, power, and the human future in space. It is therefore vitally important to see through the myths around him, to understand the bleakness of his vision for the future, and to present something better.

Let’s admit: Tesla does make some very cool cars. The acceleration on the Model 3 matches some of the fastest sports cars in the world. When Consumer Reports tested the Model S, the car “performed better in our tests than any other car ever has.” This has made Tesla useful in hastening the global transition to renewable energy and zero-emissions vehicles. Once upon a time, electric cars were seen as crunchy and uncool. Tesla made electric sexy, futuristic, and desirable. A Tesla SUV can beat a muscle car in a drag race. They’ve helped to make electric cars that a person who doesn’t care about electric cars might buy, and they’ve contributed to the emerging consensus that it’s only a matter of time before internal combustion engines are entirely outmoded. (It’s a good sign when YouTube Car Guy Jay Leno—hardly an environmentalist—is telling his millions of Car Guy viewers that they’d better resign themselves to the fact that they are going to be driving electric soon, but that this is alright, because they’ll be driving Teslas.) Now, as we’ll see, Tesla is also frequently deceptive and in many ways inept. Yet it’s a fact that the company has revolutionized electric cars, and the established automakers are only just beginning to catch up.

But then we have Elon Musk himself, who is constantly saying incredibly dumb things. Every time I hear him talk I am impressed by how unimpressed I am. The first time was when I read his comments on why the United States was “the greatest force for good of any country that’s ever been,” citing our participation in both World War I and World War II as examples of the U.S. “saving democracy.” Not everyone can be expected to have read Chomsky, but one might at least expect someone who is going to publicly express opinions on historical events to understand the causes of World War I. On the scale of ignorant Musk comments, however, this one turns out to barely even rank. His takes on the COVID-19 pandemic make Donald Trump look like the dean of Harvard Medical School. “The coronavirus panic is dumb,” he tweeted early on, and “danger of panic still far exceeds danger of corona… If we over-allocate medical resources to corona, it will come at expense of treating other illnesses.” Musk predicted that by April 2020 there would be zero daily cases, and said that “kids are essentially immune to the disease.” More than 500,000 deaths( in the U.S. alone) later, this looks very, very foolish.

On Twitter, Musk has become infamous for comments that are juvenile (“69 days after 420 again haha”), offensive (“I absolutely support trans, but all these pronouns are an esthetic nightmare”), and flat out wrong (COVID is a “specific form of the common cold.”) A former Tesla executive told Vanity Fair that “there were times Musk would say or tweet something that was just too embarrassing to even try to defend.” At one point, “Twitter shut down his account, assuming it had been hacked,” when Musk began posting “pictures of manga women with captions like ‘im actually catgirl here’s selfie’ and solicitations to buy bitcoin.” Musk’s account was restored when he confirmed the posts were authentic.

Musk’s itchy Twitter-finger has had some unfortunate consequences for his company, as when he infamously falsely tweeted that he had secured funding to take Tesla private, which landed him a $20 million fine from the Securities & Exchange Commission, and when he tweeted that Tesla’s stock price was too high, which instantly wiped $15 billion off the company’s value. When a group of Thai schoolchildren were stuck in a cave, Musk not only pretended that he personally would save the children with a special mini-submarine—he did not—but smeared one of the actual cave rescuers as a pedophile.

Reports from inside Tesla confirm what we might expect, which is that Musk is a genuinely awful boss who throws fits and treats people abominably. A WIRED report based on conversations with those close to Musk describes what is politely labeled “a high level of degenerate behavior” and which one person in Musk’s circle describes as “total and complete pathological sociopathy.” One engineering executive said: “If you said something wrong or made one mistake or rubbed him the wrong way, he would decide you’re an idiot and there was nothing that could change his mind.” During a temporary production problem, Musk strutted onto the factory floor, “red-faced and urgent, interrogating workers he encountered, telling them that at Tesla excellence was a passing grade, and they were failing; that they weren’t smart enough to be working on these problems; that they were endangering the company.” WIRED reports that he picked on one young engineer, asking vague questions, and when the worker looked puzzled, shouted, “You’re a fucking idiot! Get the fuck out and don’t come back!” Random firings like this are apparently not uncommon—he was “so prone to firing sprees that Tesla employees were told not to walk past his desk in case it jeopardized their career.” One former Tesla executive says Musk is even known to come to work saying, “I’ve got to fire someone today,” resisting those who politely point out that there is no need to fire people for the sake of it.

Reports overflow with the kind of spoiled child behavior that only the super-rich can get away with, because only the super-rich are surrounded by flunkies who do not dare push back. Sometimes it genuinely seems as if Musk is the protagonist of a film about a middle schooler who is put in charge of an auto company. On an earnings call, Musk refused to answer “boring bonehead questions” about such matters as the company’s future capital needs, once again causing the stock to drop. His insistence that the Tesla Model X have “falcon wing doors” turned into an engineering nightmare.

Musk subscribes to the theory of management that the Vision matters far more than such trivialities as reasonable hours and safe working conditions. Workers have called the factory “a modern-day sweatshop.” Musk had little interest in trying to keep them safe from COVID-19, forcing them to keep working, resulting in 450 coronavirus cases. Dangerous conditions didn’t begin with coronavirus; in 2019 Forbes reported that Tesla outpaced rival automakers in racking up workplace safety investigations and violations, with 24 investigations and 54 violations from California’s Occupational Health and Safety Administration over a four-year period. Even when Tesla’s unusually high rates of workplace injuries improved, a Reveal News investigation showed that the company had been cooking the books, “fail[ing] to report some of its serious injuries on legally mandated reports, making the company’s injury numbers look better than they actually are.” One former environmental compliance manager was shocked at the conditions, and wrote an “alarmed” letter to HR saying that “the risk of injury is too high… people are getting hurt every day and near-hit incidents where people are getting almost crushed or hit by cars is unacceptable.” Incredibly, she was told by the safety team that “Elon does not like the color yellow” as an explanation for the failure to put brightly-colored warnings. He also didn’t like “too many signs” or “the warning beeps forklifts make when backing up,” and these “preferences… led to cutting back on those standard safety signals.”

Naturally, Musk has aggressively squelched union organizing at Tesla. He falsely accused a worker of being a paid union agitator, and workers report that “anything pro-union is shut down fast.” In March, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruled that Tesla had engaged in unfair labor practices, disciplining or even firing workers for union organizing in direct violation of federal labor laws. Musk also sent a tweet implying that if workers unionized, Tesla would take their stock options away, which the NLRB has demanded be deleted. Musk had previously lambasted unions in correspondence with workers, promising them free frozen yogurt instead.

All of this would be just another tale of how Silicon Valley Geniuses are cruel and stupid in private—and how companies that portray themselves as ethical world-changers are internal dictatorships. But Musk is more than a CEO, he’s a hugely influential public Visionary. Essential Magazine says that, “In an age when we desperately need visionaries to lead the way, Elon Musk is a multidisciplinary engineer, inventor, entrepreneur and futurist with the drive to do what today’s politicians can’t – change the world for the better.” When Musk issues a pronouncement or prophecy—e.g. “A Million Humans Could Live on Mars By the 2060s,” “Artificial intelligence will be superior to humans within five years”—it is often reported uncritically in the press, as if the very fact of his believing something makes it newsworthy. The Washington Post says he is “arguably the world’s most important entrepreneur,” and the Guardian describes him as a man with a “desire to push the limits of what was possible for private enterprise… the archetypal serial entrepreneur.” Musk inspired Robert Downey Jr.’s portrayal of billionaire superhero Tony Stark in Iron Man. Musk’s hagiographer, Ashlee Vance, writes that he is “the possessed genius on the grandest quest anyone has ever concocted” (Vance’s book is called Elon Musk and the Quest for a Fantastic Future.) Four different children’s books aim to inspire young people to be more Musk-like, including Elon Musk: What YOU Can Learn From His AMAZING Life. The New York Times says reading of Musk’s life should imbue us with “a sense of legitimate wonder at what humans can accomplish when they aim high, and aim weird.”

Musk is not just admired for improving electric cars and privatizing the work of NASA, but for his forward-looking philosophy that dares to dream of transformative new human achievements. As Essential put it, we “desperately need” visions, and, well, at least he’s got one. Unfortunately, it’s bleak. Much of it seems to center around colonizing Mars, where Musk has vowed to send millions of people. Like Jeff Bezos, he appears to believe in a future of privatized corporate space colonies. He has said that on Mars, SpaceX will be subject to its own laws and free of international jurisdiction (legal experts call this “gibberish”). He has even suggested a kind of indentured servitude program whereby people take on debt by going to Mars and then work it off.

None of it is likely to happen. But Musk is likely to shape people’s views of what possible human futures can and should be like. And the one he imagines is a dystopian one. In fact, the very reason he wants to go to Mars is that he believes it is important for the “continuance of consciousness” when human beings destroy themselves in World War III. Now, I certainly share the fear of human self-annihilation, but Musk (like many other billionaires) seems to treat some kind of apocalypse as almost inevitable and think we’d better spend time plotting escape routes for the rich, rather than working toward world peace, stopping climate change, and eliminating nationalism.

You can see Musk’s dystopianism in the design for Tesla’s much-ridiculed Cybertruck, which looks to me like the preferred conveyance of 22nd century cyborg death squads. Legendary auto designer Frank Stephenson (of BMW, McLaren, Ferrari) says in a blistering review of the Cybertruck that it shows brutality and paranoia (Musk has emphasized how bullet-resistant the truck is, as if we are resigned to a future of shooting each other on the highway.) Stephenson points out that the Cybertruck shows the bad kind of futurism, the kind that believes the future is something that happens to us, rather than that we dream and then create ourselves—meaning that a “futuristic” design is one that looks like “what we think the future is going to be” rather than what we want the future to be. Musk has said that “you want to wake up in the morning and think the future is going to be great.” But for Musk, this seems to mean maintaining same neo-feudal social relations, but with the cyberpolice driving sustainable electric death-mobiles.

It makes me deeply sad that Elon Musk is seen by many as our biggest Dreamer, because his dreams are so pitiful. Because he is a 12-year-old, they often just involve having the same shit, but bigger and faster, rather than actually doing the hard imaginative work of figuring out how to solve our hardest social problems. Take Musk’s approach to transit. His company has improved electric cars, but he doesn’t have any idea how to address the problems flowing from car culture. Musk has insisted repeatedly that the solution to traffic problems, from California to Miami, is to simply dig tunnel after tunnel after tunnel. He has even started a tunneling company that proposes to solve urban transit problems, which has been given a nearly $50 million contract by the city of Las Vegas to construct a short (less than 1 mile) tunnel around the city’s convention center. It’s being billed as an “underground people mover,” but Curbed notes that “what’s being built appears to be more of a mechanism for giving one-minute test rides in Teslas” (on the city’s dime, of course). Other tunneling plans have already been scaled back or abandoned.

There are two interesting things about Musk’s tunnel schemes. The first is that they can’t work, and the second is that there is something else that can. YouTuber Justin Roczniak aka “donoteat01” has an excellent explainer video going through the flaws in Musk’s plan to relieve urban congestion through tunnels. Musk proposes to shoot electric vehicles on tracks at very high speeds through extremely narrow spaces, but there are huge safety problems and logistical problems, and the tunnels, even if built, would likely just move traffic jams to the tunnel entrances. Yet some people are genuinely counting on Musk—the mayor of Miami seems to believe Musk’s promise that he can build a tunnel under the city for about 5 percent of the cost initially estimated by local transit officials.

Everyone wants a cheap and easy solution to extremely difficult problems. Roczniak usefully uses the distinction between “AM” and “FM,” which in this case stand for “Actual Machines” and “Fucking Magic.” In the world of Actual Machines, engineering is slow and difficult and costly and often boring. In the world of Fucking Magic, all you need is a concept and a cool-looking rendering. See, for example, Musk’s “Hyperloop,” which was proposed to great fanfare in 2013 as an alternative to building high-speed rail (it would shoot people in an enclosed tube at 650+ miles per hour). Talk of the hyperloop has since dissipated, and it now appears to have been reconceived as the plan to drive ordinary street cars in a tunnel. The Daily Beast reports that excitement about the loop appears to have fizzled as plans “slam into cold hard reality,” and when Musk invited the press to a demonstration, “instead of a pod rocketing passengers at high speeds, reporters climbed into electric cars made by Musk’s Tesla and were treated to a 40 mph ride along a bumpy path.” (Strong echoes of the Simpsons’ Lyle Lanley here.)

What is frustrating is that there are already known ways to improve transit infrastructure, namely through subways, buses, and trains. But Musk hates public transit, and has never disguised his feelings:

I think public transport is painful. It sucks. Why do you want to get on something with a lot of other people, that doesn’t leave where [sic] you want it to leave, doesn’t start where you want it to start, doesn’t end where you want it to end? And it doesn’t go all the time. […] It’s a pain in the ass. That’s why everyone doesn’t like it. And there’s like a bunch of random strangers, one of who might be a serial killer, OK, great. And so that’s why people like individualized transport, that goes where you want, when you want.

Of course, there are plenty of reasons people like public transit. If the network is good, then it does go where you want it to go, it does go regularly, and you don’t have to hunt for parking when you get there. And it’s far better than being stuck in traffic. Musk, who says that he wants to get the economy off fossil fuels and end traffic congestion, is only willing to entertain solutions that don’t require rich guys to come face to face with commoners—who, after all, might be serial killers. Plus, because Musk is a 12-year-old, the quotidian world of planning departments, transit authorities, and city traffic engineers bores him. Does it have falcon-wing doors? No? Booooooring.

Musk’s preference for hype and exaggeration over follow-through and diligence has created a great deal of dysfunction within Tesla, as journalist Edward Niedermeyer reports in Ludicrous: The Unvarnished Story of Tesla Motors. Little that Musk says can be trusted. He has promised to fill space with his satellites to provide a powerful new alternative internet infrastructure—but this isn’t going to happen, though it may well massively inhibit the ability of actual scientists to do their work and ruin the night sky. His Neuralink company talks of uploading brains to computers and implanting chips that will be “like a fitbit in your skull”—but this is unlikely to happen either, and the MIT Technology Review says what has been revealed so far is “neuroscience theater” with little evidence to back up Musk’s astonishing promises. From the announcement that Tesla would switch to building ventilators to help COVID patients to the “mini-sub” that proved inferior to old-fashioned diving skill in the cave rescue, Musk comes up with flashy world-saving schemes one after another and rarely delivers. (Some of the schemes aren’t world-changing, just obviously doomed, as when he attempted to launch a competitor to The Onion called Thud.) Niedermeyer notes that, “Each of these announcements struggled to withstand close examination, ranging from mere exaggeration to quasi-delusional fantasy” but “many outlets reported these developments unquestioningly,” contributing to Musk’s “legend as a twenty-first-century Renaissance man.” So many of these plans are from the “FM” world, and when you read analyses by science and tech writers from the “AM” world, you realize that the line between Elon Musk and Elizabeth Holmes is thinner than you might think. (When the Barnumesque BS is exposed, it can be extremely amusing, as when in a live demonstration, the “armor glass” windows on the Cybertruck were easily smashed.)

Niedermeyer documents the way that Musk’s claims sometimes border on outright fraud. Niedermeyer believes Tesla may well have pretended it could charge cars faster than it could in order to qualify for a state tax incentive scheme, and as he reported began to see that “potentially massive gaps existed between Tesla’s carefully cultivated image and reality—yet the company was capable of saying and doing whatever it thought it needed to maintain its reputation.” Tesla even required some owners to sign non-disclosure agreements when it agreed to repair problems with their cars, which created a minor scandal when it became clear that the agreement’s text would keep people from being able to tell government regulators if there was a safety issue. Niedermeyer also reports a shocking incident in which Musk personally called the employer of a blogger who had been debunking Musk’s claims online (the blogger was anonymous but had been doxxed by Musk’s fans). Musk threatened vague legal action, and the employer asked the blogger to stop commenting on Tesla, which he did. (Niedermeyer says the company has also repeatedly engaged in “blatantly defamatory smear[s]” of journalists who report critically on it.)

Sometimes the misrepresentations are extremely dangerous. Musk has long been obsessed with fully autonomous self-driving cars, and has been on a mission to beat Google in developing the technology. In Niedermeyer’s words, to do this Tesla tried to“develop a product that would create the impression of a self-driving car as quickly as possible without tackling the toughest safety challenges…” Tesla even sold drivers on the idea that its existing cars have an actual “full self-driving mode,” and Musk strongly implied that the cars did not need drivers. This turned out to be a huge exaggeration—there is a world of difference between the kind of augmented cruise control that exists today and a fully self-driving car. But Musk, wanting to show that Tesla had beaten Cadillac’s Super Cruise system, made grandiose claims. He had to make “the system seem more advanced and autonomous than anything else on the market” because otherwise “Autopilot would be almost impossible to distinguish from any other ADAS [advanced driver assistance system], and Tesla’s supposed advantage in autonomous-drive technology (and the billions in market valuation that it brings) would disappear.” There was internal dissent among engineers about Musk’s insistence on branding the system “self-driving,” with some resigning and one criticizing “reckless decision making that has potentially put customer lives at risk.”

Indeed, customers’ lives were very much at risk. Tesla drivers took Musk’s claim of an “autonomous” car seriously, and some over-relied on the system and got themselves killed. Now, sensible auto journalists are even refusing to use Tesla’s term “Full Self Driving Mode,” believing that it is false and dangerous. Musk has nevertheless charged customers $10,000 each for the promise of a “fully self-driving” feature on their cars. The fact that no such car is here, and none appears likely to be here soon, means there is already talk of class action lawsuits among those who forked over large sums on the assumption that when Musk said the cars would drive themselves he meant it. As Jalopnik asks: “Is [full self-driving] a genuinely earnest project with real goals and deliverables, or an elaborate scam to get a lot of money while delivering nothing?” If the latter, it’s the kind of deception that one might expect to result in a criminal trial—Elizabeth Holmes is currently facing felony charges for misleading people about what her blood tests could do. But Musk seems to skate through every scandal.

Of course, one of the biggest Musk Myths is that he is a self-made entrepreneur, whose work shows what “private enterprise” can accomplish. Despite Musk’s contempt for regulations, Niedermeyer shows that Tesla was unable to survive in the free market, and only exists today thanks to a $350 million Department of Energy loan that came at a crucial time. A Los Angeles Times investigation in 2015 revealed that Musk’s empire was built on $4.9 billion in government support. People were able to buy expensive Teslas, for instance, partly because the government paid them to buy electric cars in the form of tax credits. Travis County, Texas, “has offered a $14.7 million (at minimum) tax break for the building of a Tesla factory” and “[a] Nevada factory was built on the promise of up to $1.3 billion in tax benefits over two decades.” Now, with Joe Biden’s giant infrastructure bill set to give out $174 billion more in electric vehicle investments, Musk is sure to receive a new windfall.

It’s good that the government stepped in to make electric cars more attractive. Supporting innovations that the market doesn’t find profitable is part of what the state is for. But the fact that Musk takes public money while presenting himself as the heroic libertarian opponent of stodgy government bureaucracy is maddening. So, too, is the fact that he, rather than the public, is the one who ends up getting rich. (Ah, but he told Bernie Sanders he is only “accumulating resources to help make life multiplanetary & extend the light of consciousness to the stars.”) And if present trends continue, cities may end up giving Musk giant sums of money based on promises he has no intention of fulfilling, and our space exploration budget may go to help Musk set up his sky-polluting for-profit satellite company and quixotic “space servitude” mission to Mars.

It’s easy to see how the myth of Musk as a planetary visionary has survived. First, unlike Elizabeth Holmes, Musk has actually done some of what he has promised, and often despite great odds of failing. Niedermeyer notes that succeeding as a startup in the auto industry is devilishly difficult, because of the immense capital expenditures required. It’s not like producing a piece of software, when once you’ve made it, it can be copied infinitely. Once you’ve got a brilliant prototype car made, then the difficult part begins, which is figuring out how to mass-produce the thing. Tesla may have missed production targets and had quality control issues, but they have been competing against centuries-old car companies that have had many generations to iron out kinks in the production process. True, Niedermeyer reports that Musk seemed uninterested in adopting industry best practices and proven quality control measures. But it’s not all smoke and mirrors, and if Tesla begins deploying its electric semi trucks, it will do something to curb emissions. I want the damn company to succeed.

But there is clearly a serious problem with the notion of Musk as a Genius Visionary. First, it’s not clear how much those he employs succeed because of him rather than in spite of him. Clearly some of it is just horrible management—wild firing sprees based on nothing except the desire to wield power do not do anything to help an enterprise flourish. The CEO of a company frequently gets undue credit for the labor of the diligent but non-publicity-seeking workers who are mostly responsible for the institution’s accomplishments. (Musk began actively trying to diminish the degree of credit others got for Tesla’s work early on, according to Niedermeyer, and he fought to become listed as a co-founder of the company, even though he wasn’t.) One engineering executive said that “when people were shielded from Elon, Tesla was amazing” and did “incredible things.” I believe it, although I can also believe those who say they were inspired by Musk’s insistence on objectively impossible things. There can be some positive consequences to having an institution ruled over by a demented child-emperor. Sometimes the child demands the impossible, but then all the smart people have to figure out how to do something approximating the impossible and appease the child. Ultimately, I think democracy is a much more stable and just form of government, and do not think the benefits of being ruled by a tyrannical madman outweigh the considerable costs.

The idea of “genius,” even of being “smart” itself, also needs to be ditched, because it implies that if someone is impressive at some narrow task, they are Intelligent and thus worth listening to on subjects going beyond their tiny area of expertise. Timothy L. O’Brien, of Bloomberg, laments the way Silicon Valley techno-kings’ “observations about the social order and commonweal get more attention and take on more gravitas than they deserve, boosted and hurried along by the idea that great wealth confers great wisdom.” In Musk’s case, a certainty about his genius results in an indulgence of his cruelty and a lack of scrutiny of his delusional (sometimes even dangerous) schemes. I have read reports of those who worked with Musk calling him the “smartest guy in the room,” and while I believe that they believe this, it’s important to note that the guy nobody is allowed to question for fear of losing their job will often appear to be the smartest guy in the room when he is just the most powerful. One reason Elon Musk has succeeded is that in many ways, our economy rewards those who create the appearance of value rather than actual value. Tesla’s stock price baffles analysts—its “valuation doesn’t make sense by any traditional measure.” In part it thrives, and Musk continues to build his wealth, because he has successfully convinced people to pin their hopes on him, because he is a genius for whom it will all work out in the end. Musk’s following is quasi-religious in nature, as anyone who has incurred the displeasure of his online fans knows all too well. But we live in the age of the NFT, when it’s easy to sell the holographic appearance of a thing rather than the thing itself. Musk is selling delusions about a future that only looks cool because the alternatives on offer are so bleak.

But we can do better. Shannon Stirone of The Atlantic contrasts the futurism of Elon Musk with that of Carl Sagan, the great humanist astronomer, who had a far more socialistic vision, one that emphasized the universe’s beauty and mystery, and the folly of our earthly power struggles:

Sagan inspired generations of writers, scientists, and engineers who felt compelled to chase the awe that he dug up from the depths of their heart. Everyone who references Sagan as a reason they are in their field connects to the wonder of being human, and marvels at the luck of having grown up and evolved on such a beautiful, rare planet. The influence Musk is having on a generation of people could not be more different. Musk has used the medium of dreaming and exploration to wrap up a package of entitlement, greed, and ego. He has no longing for scientific discovery, no desire to understand what makes Earth so different from Mars, how we all fit together and relate. Musk is no explorer; he is a flag planter.

It is natural to desire a “fantastic future.” Personally, I’m sad that we no longer have World’s Fairs showcasing what we think humankind might accomplish in the next decades. Musk fandom arises in part because he is offering something resembling a path to clean energy and space exploration, both of which are appealing and important. But it’s a mirage, and following it will take us further in the direction of dystopia. Instead, we need a humanistic vision of a high-tech future, one that rejects workplace tyrants, privatized spacefaring, and ever-multiplying underground freeways in favor of democratic governance, strong public institutions, and transit for the people. It can be done, even in the world of Actual Machines. And it can be more inspiring than anything Elon Musk has ever dreamed of.